FrontendArmory

FrontendArmoryReact, Routing and SEO

TODO

Websites and apps live and die on their traffic. And on the modern web, the majority of traffic comes from search engines and social media. If you want your site to be seen by anyone, then you need to design for SEO and SMO — and that means pre-rendering your app using static or server rendering.

There’s just one problem: real-world apps are big.

Imagine if Facebook sent all its data and JavaScript code with each request. It’d break the internet. Indeed, if you take a look around the industry, the vast majority of real-world apps rely on some kind of asynchronous data — whether it’s fetched from an API, pulled from a database, or dynamically imported from code-split bundles. For the most part, React handles this asynchronous data pretty well; hooks or lifecycle methods make it easy to show a loading spinner until the data is ready. But there’s a catch.

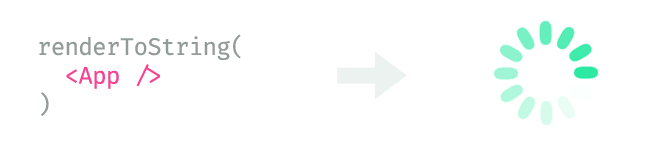

Outside of the browser, hooks and lifecycle methods don’t work so well. This is because React takes a completely different approach to rendering; on the browser, you call ReactDOM.render(), while on the server, you use ReactDOMServer.renderToString(). And while renderToString() will happily render your page’s initial content, this doesn’t help when the initial content is a loading spinner.

Now as you probably know, the React ecosystem does have a number of tools that help with pre-rendering and asynchronous data. For example, Apollo gives you renderToStringWithData(), Next.js gives you getInitialProps(), and Gatsby lets you hide the filesystem behind a special GraphQL layer. And while these approaches each have their upsides, they also add a huge amount of complexity; from the huge assumptions that Apollo makes about your backend, to the entire framework and build systems behind Next.js and Gatsby.

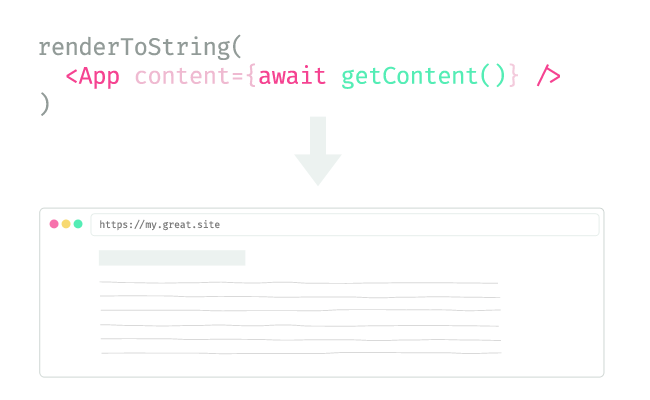

But let’s forget all that, and focus for a moment on the core problem: React is (for the moment) synchronous. Your content needs to be available immediately upon calling renderToString().

What if all you really needed was a way to get your page’s content before calling renderToString()?

#Fetching Content

So you want to fetch your entire page’s content. Let’s discuss some ways you could go about this.

#The GraphQL Way

GraphQL, as the name kinda gives away, is a query language. It lets you select a small set of data from a big set of data, just by naming the data that you want.

For example, here’s a query that you might use with Gatsby — a CMS with great GraphQL support. You can imagine that this query is like saying “hey Gatsby, the Home page needs to know the site’s description, so please make sure that it’s available for me.” And Gatsby obliges.

query HomePageQuery {

site {

siteMetadata {

description

}

}

}Ok, neat. So GraphQL lets you declare the content that is required by a page, so that it can be fetched ahead of time. There’s just one problem. Ok, there are actually multiple problems, but let’s focus on this one:

What if your content needs to be run as JavaScript instead of being read in from a GraphQL store? What if your content is code?

“Yeah but James, nobody is going to use code for content.”

So actually, there’s this neat tool that you might have heard of called MDX. It lets you use JSX within Markdown, and in order to make that work, it actually compiles Markdown files into React components. It compiles your content into code. And to make that (half) work with GraphQL, Gatsby’s MDX plugin uses eval new Function():

// children is pre-compiled mdx

const keys = Object.keys(fullScope);

const values = keys.map(key => fullScope[key]);

const fn = new Function("_fn", ...keys, `${children}`);

const End = fn({}, ...values);

return React.createElement(End, { components, ...props });Obviously, not every app needs to use MDX — but there are many other types of code that you might want to load at runtime. You might want to split components, or reducers, or styles — or even entire routing trees out into separate chunks that are dynamically imported. And while GraphQL is great for many situations, there are times when you’ll need more power of how your content is loaded.

#The Next.js Way

Next.js has a different solution for loading your content: it lets you specify a getInitialProps() async function on some components.

function TheGreatestSongInTheWorld({ songName }) {

return <div>This Is Not The Greatest Song In The World: {songName}</div>

}

TheGreatestSongInTheWorld.getInitialProps = async ({ req }) => {

const res = await fetch('https://greatestsongintheworld.com/api/v1/song')

const json = await res.json()

return { songName: json.songName }

}This function is called by Next.js before the components are first rendered, and since it is an async function, it can take as much time as it pleases. In fact, by virtue of being a plain old function, getInitialProps() can do whatever it damn well likes. It can wait for dynamic import() expressions, it can fetch() data from a server — it can even query a GraphQL store. Naturally, it can also return MDX components.

Ok, but say that your app has more than one component. How does React know which getInitialProps() functions to call, and which ones to leave alone? Have a think about it, then click the spoiler to gain the hidden knowledge within.

Actually, that was a trick question. React doesn’t even know that getInitialProps() exists — it’s a Next.js thing.

React doesn’t call getInitialProps(); Next.js does. And to decide which getInitialProps() function to call, it uses its router. It follows this process:

- Look at the current URL.

- Looks for a file within your source’s

pagesdirectory with a name that matches that URL. - Call the

getInitialProps()function for the component exported by that file.

Where GraphQL lets you select data from a store, a URL lets you specify what data you need full stop. In fact, when you think about it URLs are actually queries — along with the rest of a HTTP Request, they let you declare the content you want from a web server.

Given that the a URL is like a query language for pages, it makes perfect sense to use a page’s URL to decide which data will be fetched before rendering. And that’s exactly what Next.js does. It uses its router to find the getInitialProps() function that can get your page’s content, and once the content is available, it renders the page with React.

Of course, this approach has some limitations. In particular, it ties the required data to the concept of pages — top-level components that live in a specific location on the filesystem. It forces you to fetch all your data for each page in one monolithic getInitialProps() function — a big structural (and philosophical) departure from the granular, component-based structure of your typical React app.

#Composability vs. Flexibility

It’s my feeling that the GraphQL approach provides superior composability to Next.js. With some hackery, it becomes possible to automatically prefetch all GraphQL queries across an entire component tree. However, in the flexibility deparment Next.js wins hands down; you have the full power of JavaScript to fetch your content, whether it takes the form of JSON, code, or even something sent over websockets.

So you get a choice: composability, or flexibility. But why should you have to choose? Ideally, you’d have composability and flexibility. So let’s rewind for a moment and ask the question again:

How can you get your page’s content before calling renderToString()?

As you’ve seen, it turns out that a URL gives you all the information you need to get a page’s initial data. So even without the heft of Next.js or Gatsby’s build systems, you should theoretically be able to get your content as a function of a URL, and some “routes” that define the mapping between URLs and content:

// Given some route definitions and a URL, get a "route" object

// containing everything needed to render the page.

let route = await getRoute(routes, url)

// Now that you have the data, render it!

ReactDOMServer.renderToString(<App route={route} />)In the above example, I’ve called your content a route object, but you could call it anything. The important thing is that it contains all information that is necessary to synchronously render the page, including:

- The page’s

<title> - Any

<meta>tags - Any data fetched from remote servers

- The results of any GraphQL queries

- Any React components that need to be loaded asynchronously

- The React elements that will actually be rendered

So far, so good — we’ve got the beginnings of an API that provides many of the benefits of Next.js, without all of the build system baggage. But getRoute() is still a single function, like getInitialProps() — how are we going to make routes compose?

#The Navi Way

Navi is a JavaScript library for mapping URLs to content; it’s a router. But unlike Gatsby and Next.js, it’s just a router. It doesn’t make any assumptions about a top-level “page” object, nor does it make any assumptions about your filesystem layout.

While Navi comes with a static rendering tool, it’s completely optional. In some ways, Navi has more in common with routers like react-router and @reach/router than with frameworks like Gatsby and Next.js. It gives you primitives like lazy(), mount(), redirect() and route(), and lets you use these to declare a routing tree that maps URLs to (possibly asynchronous) content.

let routes = mount({

'/': redirect(async () => {

let latestPostId = await getLatestPostId()

return '/posts/'+latestPostId

}),

// `mount()` can be nested allowing for routing trees to be reused

// across apps, languages, etc.

'/pages': mount({

// `lazy()` allows you to load more routes and mounts as they're

// required, allowing for arbitrarily large routing trees.

'/about': lazy(() => import('./aboutRoute')),

}),

'/posts/:id': route(async (request) => {

let post = await getPost(request.params.id)

return {

// The browser's document title will automatically be updated

title: post.title,

head: <meta name="description" content={post.description} />,

data: post,

view: <Post />,

}

})

})The four routing functions in the above example give you a lot of declarative power — lazy() in particular is a boon for performance tuning. However, they still don’t give a huge advantage over Next.js. For that, you’ll need Navi’s with functions:

withContext()withData()withView()- etc.

These functions can be composed with the basic routing primitives like mount() and route(), allowing you to pass information down the routing tree, and to create nested layouts.

compose(

// Pass information to child routes

withContext(async () => ({

currentUser: await getCurrentUser(),

})),

// Wrap child routes with a layout component

withView((request, context) =>

<AppLayout currentUser={context.currentUser}>

<View />

</AppLayout>

),

// Any routes mounted under here will be rendered within the above

// layout, and will have access to the above context.

mount({

'/settings': route(async (request, context) => {

return {

view: context.currentUser ? <Settings /> : <Login />

}

})

}),

)In fact, Navi even allows you to switch entire routing trees at runtime, using a function called map(). This is invaluable for implementing authenticated routes. And once you have a routing tree, actually getting the current route is literally as easy as awaiting a promise:

let navigation = createMemoryNavigation({ routes, url })

// This will return a `Route` object containing everything that Navi knows

// about the specified URL, including title, data, views, etc.

let route = await navigation.getSteadyValue()Of course, you don’t have to do this manually, because Navi also comes with a static rendering tool that works alongside create-react-app. It lets you can keep on using the tools you know, without even ejecting. Navi also comes with a set of modern React components and hooks so that you don’t have to manually work with navigation and route objects — and which let you display loading.

#Ok, but I just want a React app with great SEO

Let’s rewind back to that original question one last time:

What if all you really needed was a way to get your page’s content before calling renderToString()?

If that’s the case, then Navi is exactly what you need.

But maybe that’s not the case. Maybe all your content fits comfortably within the GraphQL format, and Gatsby just makes sense. Maybe the Webpack configuration offered by Next.js is too good to say no to. Maybe you don’t even need pre-rendering or SEO, and @reach/router is perfect for your needs. In any of these scenarios, you’ll do great without Navi.

But say that you’re building a big site and you want control over your own server or build system. Or perhaps you have a create-react-app project, and you want to add static rendering. Maybe you need the ability to load entire routing subtrees on demand. In any of these cases, Navi is perfect — and you might just want to take a look at it in a little more detail.

About James

Tokyo, Japan